The legacy of Thomas Sankara is filled with just as much tragedy as legend. His death was undeniably a setback for African independence and the struggle against the forces of colonialism.

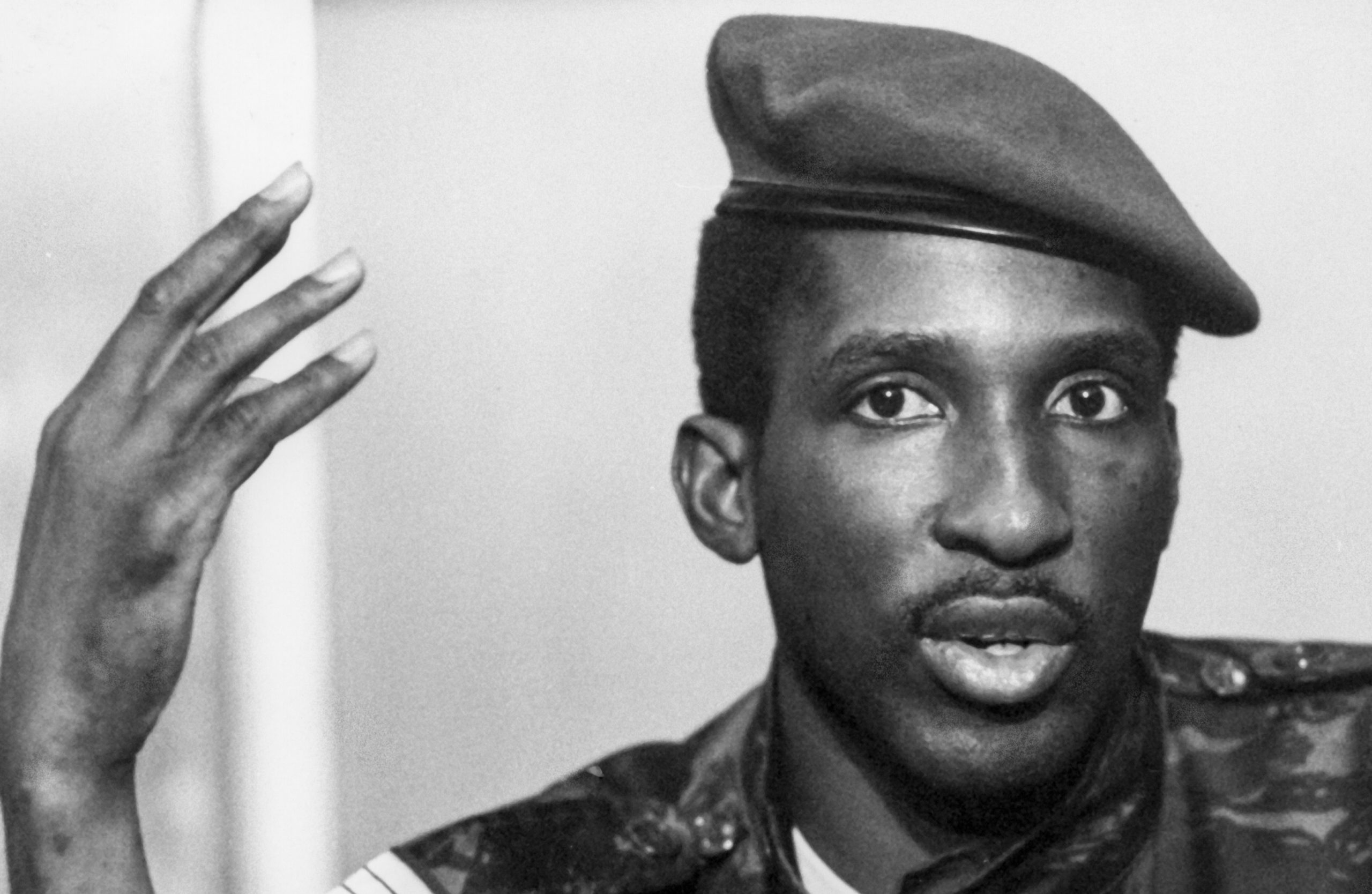

At the time of his death in 1987, Nelson Mandela was in jail, Patrice Lumumba was long dead, and for an African child in search of African heroes, the incorruptible and young soldier-statesman was a star, a guitar-playing rebel in fatigues who troubled the consciences of the powerful elites in his country and across the continent.

A transformational leader…

Sankara’s visionary leadership turned his country from a sleepy West African nation with the colonial designation of Upper Volta to a dynamo of progress under the proud name of Burkina Faso (“Land of the Upright People”). He led one of the most ambitious programs of sweeping reforms ever seen in Africa. It sought to fundamentally reverse the structural social inequities inherited from the French colonial order.

The young army captain came to power in a military coup in 1983 and inherited an incredibly abject and impoverished nation, one devastated by the effects of imperialism.

Sankara was deeply influenced by his study of Marxist revolutions. He urged every village and city in Burkina Faso to organize into committees for the defence of the revolution, local bodies that promote social welfare. Across the country, people came together to build schoolhouses, health care centres, dams, water reservoirs, and irrigation systems. Sankara nationalized all land and invested heavily in agriculture.

According to Ernest Harsch’s book Thomas Sankara: An African Revolutionary, cereal production increased by 75 percent during the first three years of his presidency, an astounding gain for a country where most people were subsistence farmers.

His goals were simple:

- eliminate corruption

- establish Burkinabe sovereignty from the West

- raise social and economic conditions

As president of one of the poorest countries in the world, Sankara believed fervently that Burkina Faso could learn to sustain itself without foreign aid. He refused aid packages from the International Monetary Fund that, he said, came with strings attached. As he famously proclaimed, “The one who feeds you usually imposes his will upon you.”

At the summit of the Organization of African Unity in July 1987, he tried to persuade other African countries to collectively refuse to pay their financial debts to their former colonizers.

The origins of debt go back to colonialism’s origins. We cannot repay the debt because we are not responsible for this debt. On the contrary, others owe us something that no money can pay for. That is to say, the debt of blood.

he said, his voice brimming with emotion.

Objectively, Sankara was able to complete most of his objectives, in just his four years in power, and with no foreign aid at all. Here are some of his achievements;

- renamed the nation from Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, meaning “land of the upright man”

- vaccinated 2.5 million children from meningitis, yellow fever, and measles in a matter of weeks

- increased literacy levels from 13 percent to 73 percent at the time of his death

- planted 10 million trees to fight desertification

- greatly improved infrastructure, building new roads and railways

- outlawed female genital mutilation, forced marriages, and polygamy

- seized farms from feudal lords and gave it to peasants, increasing wheat production from 1700kg per hectare to 3800kg per hectare

- reduced salaries and luxuries of all public servants to promote modesty and humbleness (including his own; he even refused to use his AC unit because so few Burkinabe had that luxury)

- appointed women to various positions in the government

- converted an army provisions depot to the nation’s first supermarket, open to all

In Sankara’s Burkina, no one was above farm work, or graveling roads–not even the president, government ministers or army officers. Intellectual and civic education were systematically integrated with military training and soldiers were required to work in local community development projects.

The beginning of the end…

The brash young leader was not without flaw. Some of his policies resulted in costly missteps, such as firing politically disloyal civil servants and striking teachers, heavy-handed tactics to discipline lethargic bureaucrats, or arming partisan civilian militia. He did show an uncommon ability to publicly admit failure and take corrective measures, when persuaded of his errors. However, he made enemies abroad and within for challenging systems of power and refusing to compromise on ideals for expedient pragmatism.

There were undeniably some grim realities of Sankara’s administration, namely human rights abuses. Unfortunately, an irrefutable tenet of leftist societies surrounded by non-leftist ones is the necessity of order. In order to achieve order, you must eliminate dissent. There is no room for plurality, because plurality introduces internal conflicts, which opens the door for infiltration by the bourgeoisie.

The easiest method to achieve order is by eliminating the voices of dissent. More often than not, this results in death. Inevitably, ordinary people are swept off in this maelstrom of counter-terrorism and espionage, leaving blood on the hands of the liberators and freedom fighters.

Likewise, as time drew on under Sankara’s administration, he displayed growing autocratic tendencies, eventually outlawing unions and a free press, which impeded his efforts. He also established local tribunals, which convicted citizens of reactionary sympathies or actions, known for their often ridiculous accusations of counter-revolutionary efforts, and undoubtedly killed innocents.

Sankara’s last days

It is not difficult to notice the parallels between Sankara—chastiser of the powerful, champion of the poor, betrayed by his best friend, and martyred with twelve of his companions—and another iconic figure from the Bible.

During his tenure, Sankara made some formidable enemies. By his death, he had isolated the French neo-colonialists, traditional tribal leaders, the Burkinabe upper-middle class, and others. Their despise of him culminated in a coup, in which Blaise Compaore would seize power for the next twenty-seven years.

His death was the ultimate betrayal: the coup was led by Sankara’s trusted deputy of many years, Blaise Compaoré, the then Minister of Defence. Both had led a cadre of radical junior military officers who overthrew, with popular support, a repressive regime of more conservative generals four years earlier.

The news government led by Compaoré kept a tight lid on the news of his death. It was only after several weeks passed that the pan-African magazine Jeune Afrique published the first details of the coup. It had been a bloodbath, with soldiers loyal to Compaoré killing Sankara and 12 of his aides, and dumping their bodies in shallow graves outside the capital Ouagadougou.

In the days after Sankara’s death, people in Burkina Faso wept openly and piled bouquets and messages of appreciation on the raw red earth of his grave.

Compaoré promptly set about “rectifying” Sankara’s revolution. He reinstated many officials who had lost their jobs and overturned most of Sankara’s radical reforms. Burkina Faso once again became an obedient client of the World Bank and the IMF’s development programs—aid Sankara had eschewed in his pursuit of self-reliance.

Much to reflect on…

Dubbed as the ‘Che Guevara of Africa’, the legend and legacy of Thomas Sankara achieved something the man could not. There is nothing ‘mere’ about symbols. Our symbols tell us what we believe about ourselves, what we aspire to. The symbol of Sankara has inspired activists the world over to risk their lives for democracy and fight against a culture of impunity.

The example of Sankara—coming as it does from one of the more overlooked corners of the world—is worth holding up now at a time when moral clarity among powerful elected leaders seems particularly scarce.

The slave who cannot organize his own revolt deserves no pity for his fate. He alone is responsible for his misfortune if he believes his master’s false promise of freedom. Freedom can be won only through struggle!

Thomas Sankara