The greatness of a man who has been called the last fallen giant of the 20th century African liberation leaders, that fought tooth and nail to break the flood gates of emancipation to rain down independence on the dried out plains of colonized African lands, surely cannot be over emphasized.

The gravity of his influence found a place in the heart of many Zambians, especially those who formed his circle of peers when his body ran full of his youthful vigor, and when he had the energy to ignite impactful social movements such as the “Cha-cha-cha” civil disobedience campaign, as well as the portrayal of his rare political mastery that set him up as president of the United National Independence Party (UNIP).

Following his death on June 17, this year at the age of 97 at Maina Soko Military Hospital, there has been a proliferation of articles written about Dr. Kenneth Kaunda, from profiles to biographies, political struggles, travels and so much more.

The internet has in these few days been soaked wet with countless stories that mount into the great life lived by the noble liberation leader with a rich history on his shoulders.

However, amid the man’s countless revolutionary stories and experiences, it is pretty easy to overlook interesting factors that might strike many during this time as trivial, and yet such factors make for great stories to tell.

Take for instance the late first president’s traditional attire famously known as the Toga, and his white handkerchief. How many of us have ever paused to think about the unique implications of those things or how they single-handedly played an integral role in the president’s social identity on a global scale?

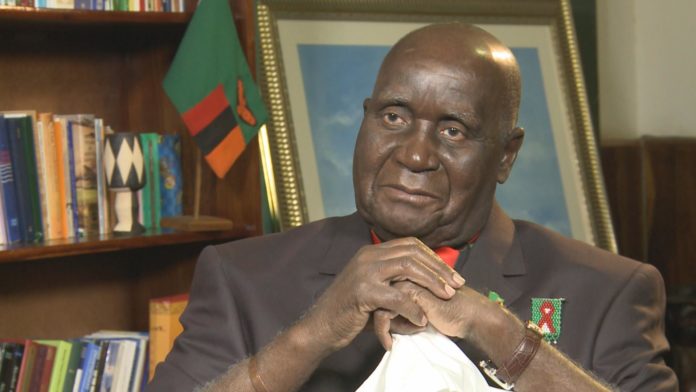

Almost like something of a peculiar superpower, in every occasion, the man always brought with him his white handkerchief.

He had it during street rallies, press briefings, his international travels, on local and international television, almost everywhere, and there seemed to have never been one day he forgot his white handkerchief.

He would wipe his face with it, use it to wave at crowds in elation, and most notably, wipe every tear shed in public and arguably in private.

The white handkerchief became so synonymous with the late first president to a point where a good many Zambians started assuming it possessed some kind of mystic supernatural powers.

A veteran by the name of Alimony Kalanga, who worked with the Zambia Police and Paramilitary in the 1960s following the first few months of KK’s presidency, recalls an interesting encounter.

It was a Saturday afternoon and the first president was just flying back into Zambia heavily guarded by the Zambia military and a handful of Zambia police officers of whom Mr. Kalanga was a part.

As was usually a custom at the time, the president was received by a number of government officials and a great number of onlookers a few meters away from his walk way, and behind him were the police and the military.

However, on this particular arrival, the onlookers standing behind a short wire fence and cheering at the president as he walked by, was a crowd of zealous Zimbabwean and Zambian freedom fighters and a few locals. The exhilarated crowd compelled KK to walk slightly closer while waving his white hankie as per usual.

Mr. Kalanga recalls that in an instant almost as if with well calculated accuracy, one Zimbabwean freedom fighter amid the cheering crowd reached out and quickly grabbed Kaunda’s white hankie right in midair as he waved.

Kaunda was caught unaware, you could see he was a bit confused and we all paused with fright and shock for a few seconds. Then immediately the officers, a few steps in front of us, leapt into the crowd, brutally grabbed the Zimbabwean man, pinned him to the ground and grabbed the handkerchief off his hands, and almost as if nothing happened, handed it back to KK, and he walked into one of the vehicles and was driven away, narrated Mr. Kalanga.

After that encounter, the veteran police officer added that the presumptuous Zimbabwean man was then dragged to the local police station for a beating over inappropriate conduct. What is interesting from this encounter however, is more than just the stunt the man pulled up but the reason he gave for why he did so.

After we took the man back to the police station and gave him some good strokes, we asked him why he did such a thing or if he was sent by forces with ulterior motives, but he just said he wanted to see what would happen to Kaunda or if he would supernaturally materialize into something else, he said.

The Zimbabwean man’s response makes it plainly obvious that KK’s hankie became something that he was closely identified with to a point where many assumed there was more to the white piece of cloth than merely something he waved around in public.

Mr. Kalanga also elaborated on how a number of passing fables began to be told surrounding the perceived mystery of the white hankie.

One such fable that held sway was a story of how a certain journalist of a local media house asked the late first president why he always carried a white hankie, then instantly the whole media house experienced an abrupt power cut.

However, beyond the surge of speculations and claims of superstition, laid the true underlying meaning to KK’s famous white hankie.

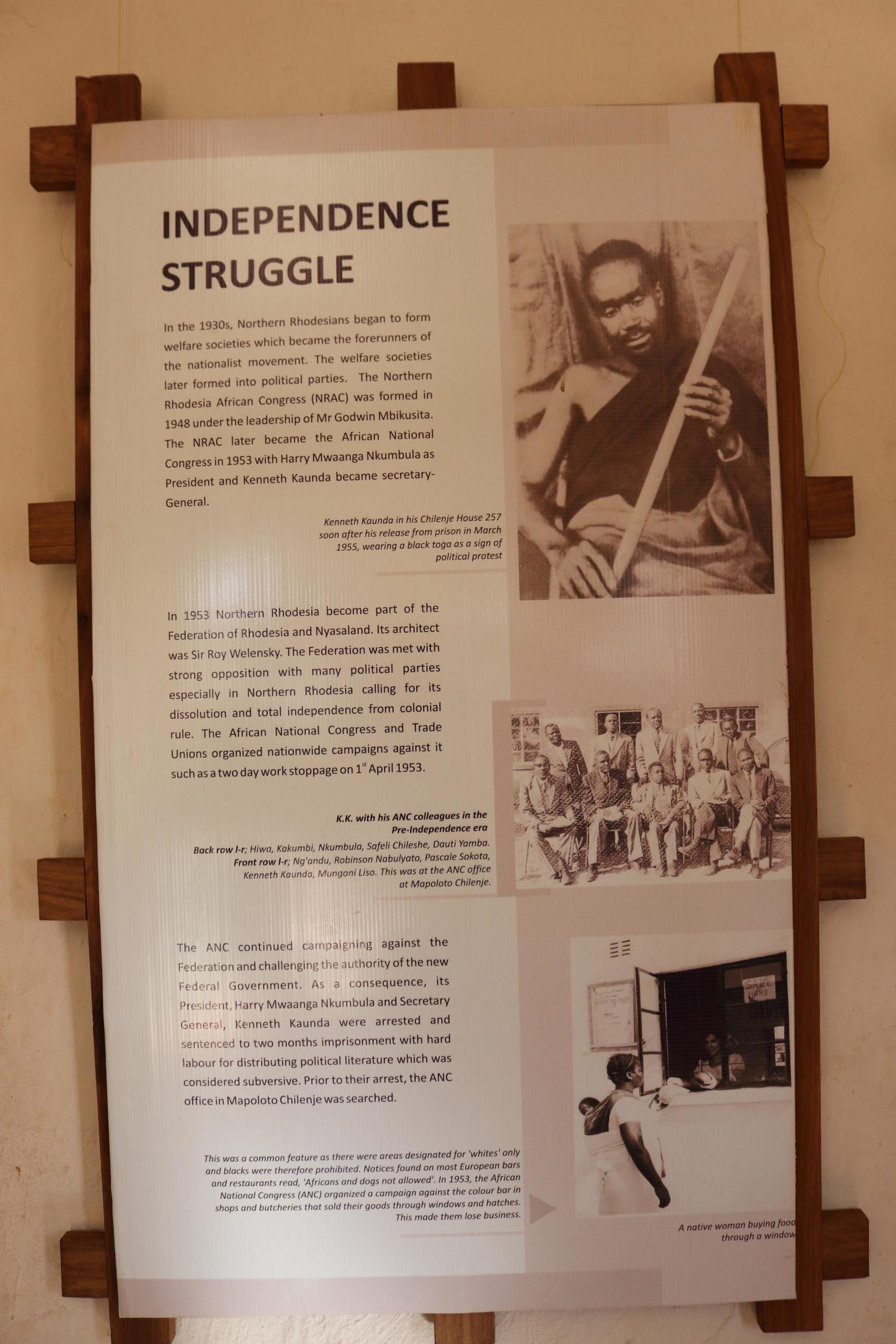

Dr. Euston K Chiputa, a historian at the University of Zambia under the Department of Historical and Archaeological Studies explained that Kaunda adopted the white handkerchief whilst in prison during the struggle for independence when he and his fellow freedom fighters were arrested by the British colonial authorities.

Mr. Chiputa added that Kaunda has had his style of a white hankie since 1960 and used it because of his insistence on peace, largely due to the influence of figures like Mahat Magandi and Martin Luther King Jr, later earning himself the nickname ‘Africa’s Ghandi.’

For Kaunda, the hankie was used to show his love for peace as well as human beings, it was a sign of a deep need to cease fighting during the independence struggle, said Mr. Chiputa.

The Historian also said that like his white handkerchief, Kaunda’s nationalistic traditional attire known as the Toga was a significant statement during the independence struggles between 1960-1964.

The Toga, though mainly associated with the former second Vice-President, the late Simon Mwansa Kapwepwe, was adopted as a symbol of authority.

KK and Simon Mwansa Kapwepwe wore the Toga quite often during the independence struggle, and even shortly after independence, KK continued to wear it but not for long, because he later on adopted his Kaunda suit, Mr. Chiputa said.

The Historian also noted that the colors of the Toga that Kaunda wore were also significant. The Toga slightly took the design of a Zebra’s black and white stripes which had a bearing on the independence struggle from white colonial masters.

Mulenga Kapwepwe, a renowned author and co-founder of the Zambian Women’s History Museum and daughter of the late Simon Mwansa Kapwepwe, said for the generation of Kaunda and the liberation leaders, their dress code was a statement.

Ms. Kapwepwe explained that their dress, particularly the Toga, spoke for their time and what they were fighting for.

Kaunda, my father and their colleagues, strived to create their own style of dress which signified everything they stood for, plus they did not want to look like the very people who oppressed them, Ms. Kapwepwe said.

She added that there was a lot of messaging and identity building in the way Kaunda and his colleagues dressed.

There was something about that generation. For instance, Ghana’s Jerry John Rawlings made the ‘Fugu,’ a Ghanaian attire that he always wore became popular among his people because it was more than a style but also a message, she said.

Ms. Kapwepwe also explained how KK’s hankie built him so much recognition to a point where people would have thought something was wrong if he was not seen with his hankie.

So unlike a force of speculation and superstition, KK’s handkerchief and his Toga were a notable part of his image and identity building that became iconic and his social signature.

Uhuru Kenyatta had his walking stick, Jerry Rawling had his Fugu, and Kenneth Kaunda had his glistening white handkerchief; this explains why a great many Zambians have been waving white handkerchiefs as they pay their last respect to the hero.

After ruling the country as Zambia’s first president for 27 years and the first founding republican president of the 1960s era to have lived long enough to witness the country’s 50th independence anniversary, Dr. Kenneth Kaunda will be remembered by Zambians in many ways more than one.

The father figure of an elated man in hairs of gray waving his white handkerchief is an image and a memory that will forever be deeply imbued in the mind of every Zambian.