The introduction of local languages as means of instruction is a good move as it will enhance the Zambian education says a linguist at UNZA, Dr. Sande Ngalande.. Sharon Mulenga, a grade two pupil at Ngwelele Primary School in Lusaka can only communicate in Bemba and Nyanja as these are the languages she is familiar with. Bemba is used at home and Nyanja is a means of communication in the community she lives. Before the change of curriculum, she had difficulties understanding concepts in class as they were taught using English.

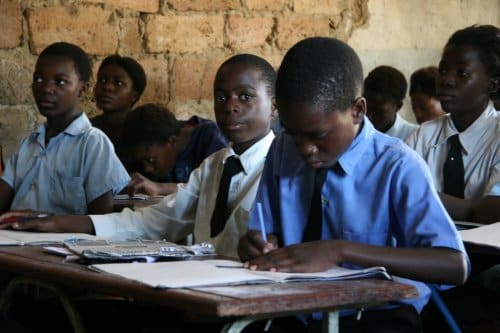

Many other Zambian children like Sharon lack adequate knowledge of the English language. Their understanding of concepts in Subjects greatly depends on the language been used as a mode of instruction.

Government, through education minister John Phiri announced new education reforms to teach all subjects in vernacular from grade one to four in all primary schools of Zambia. The seven common languages that were selected to be used for teaching in schools include; Bemba, Nyanja, Lozi, Tonga, Kaonde, Luvale and Lunda.

The just implemented policy has been received with mixed feelings from many Zambians although the Linguists are standing strong to defend this move by government. To them, this means the government of Zambia has heard the cries of the many Zambian children to legalize the use of local languages in schools as a means of instruction to the pupils.

Some say the policy is biased, incomplete, impossible to implement and also a political propaganda. But to an academician like Dr. Sande Ngalande, a linguist at the University of Zambia (UNZA), the introduction of local languages as means of instruction is a good move as it will enhance the education system in Zambia. He believes the policy was made out of research and not just a pronouncement.

Dr. Ngalande says the use of local languages in schools is not a new phenomenon in the Zambian education system.

“There was once the Zambia Primary Course (ZPC) and New Breakthrough to language Policy which was called for to ensure that the use of local languages in schools was achieved. This was said to build the vocabulary of our broken native language. The whole thing was there a long time ago”, says Dr Ngalande.

Zambia has 73 tribes of which 25 are outspoken and seven are official languages. In these terms, although 25 are the major languages, seven are seen to be subsidiaries of the 25 languages.

In a typical government school, especially in rural areas, it is practically impossible to find a Grade one pupil being taught in English all through without mixing it with a local language.

Meanwhile, a deputy head teacher at Ngwelele Primary School in Garden Compound, Bright Muhone, says the policy is welcome, as it will rebuild the language vocabulary, restore the eroded culture and enhance the levels of understanding among pupils.

Mr. Muhone adds that people should be patient as the benefits of the policy will take some time to be appreciated.

“It requires printing out of text books in local languages and relies on experts like chiefs and linguists to sit down and draw language rules. There is a lot that still needs to be done,” Mr. Muhone says.

He has in this regard registered his disappointment at those resisting the policy and the ‘unfortunate’ tendency to mistaken a common language to a mother tongue language.

“What happened on the Copperbelt province is a manifestation of lack of knowledge on the policy. The policy calls for the most spoken language to be used and not the mother tongue language”, Mr. Muhone says.

He was referring to the Lamba Chiefs on the Copperbelt province who recently resolved to reject the newly introduced government policy to teach Bemba in Copperbelt rural schools stating that it is a violation of human rights to impose a vernacular language on children not of that tribe.

Mr. Muhone further adds that a teacher can easily adapt to the change despite the burden of trying to learn a particular language as they have the ability to adjust according to circumstances. He resembles a teacher to a Carpenters’ toolbox that houses most equipment’s for his work.

A simple survey by the Lusaka Star at some of the schools in Lusaka found that teachers are ready to implement the new policy but the problem they have is lack of necessary material to use. Therefore, the teachers are using their own understanding of the native language to teach the pupils.

At Ngwerere Primary School, there was only one book written in Chinyanja being used for the grade ones. For grades two to four, the books were not yet in causing a challenge for teachers.

The major concerns of the teachers, however, are that despite the introduction of the use of the local languages in lower primary school as a means of instruction, many pupils can speak in their native languages fluently but have difficulties writing good grammar.

All in all, pupils seem happy with the new policy. Sharon Mulenga, speaking happily and proudly in Nyanja, says it is better to learn in a language that all of them understand in the classroom than using a language that can only be understood by a few in a class.